“This is a mock-up letter created to communicate with my friends soon to be and thus gone.”

Dear S. I am happy to know you are fine and I am grateful for your letter. Once again, I apologize I wasn’t able to make it to your birthday party this year. As I mentioned, your birthday weekend overlapped with a retreat I was already planning to attend for some time. I understand that this kind of absence is felt in our friendship. Because of that, I really appreciate how you ended your letter. You asked me what it means to be a Buddhist practitioner. I find your curiosity both insightful and humbling. It helps me put myself together and reflect on this intriguing path as well.

The way you framed the question made me think of how much I have been cultivating interest in matters like who or what is the Buddha, the Dharma, or the Sangha, without really attending to the people that are striving to comprehend and relate to these things. Well, I shouldn’t assume any of these make much sense to you, right? Nonetheless, they provide a good start to our conversation.

The Buddha is like a doctor. He diagnosed a condition that we all share and prescribed a treatment. The condition is called duḥkha in Sanskrit. Generally, we can understand this condition as a sense of pervasive discomfort or uneasiness. Sometimes, it is translated as suffering. Sure, it encompasses suffering. But it goes further. Etymologically, the word comes from an expression that describes an axle hole that is not in the center of a wheel. Can you imagine what it would be like to ride a chariot with such wheels? It would surely be bumpy! But not only bumpy: it would also be harder to get where we want. In sum, duḥkha is this latent feeling of never being quite there yet. A longing that something, somewhere in the future may fix the dissatisfaction in the present.

The Dharma is the treatment. In the Dharmachakrapravartana Sūtra, the Buddha sets forth the principles that guide this treatment. First, he establishes the view of the middle way. This view does not imply a sense of meek moderation. Instead of standing in the middle, we go beyond the two extremes: eternalism and annihilationism. Think of the first one as a sense of reifying the actuality of things. Phenomena – like you and me – exist, and that is final. The second, on the other hand, is a denial of this very actuality. Nothing can really be, we serve no purpose, there is no cause and effect. None of these is the Buddha’s stance on the problem. In the Mādhyamaka tradition – one of the most revered traditions of Buddhist philosophy – it is said that the Buddha’s position is beyond existence, non-existence, both existence and non-existence, and neither existence and non-existence. It surely makes our heads spin!

That said, this is the treatment rationale. The actual practice is much simpler. It can be encompassed in what the Buddha calls in the Sūtra the Noble Eightfold Path. This path consists of the right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. To avoid further complications, think of these as being guided by two simple principles: having a kind heart and a tamed mind. Our speech, actions, and livelihood should be kind and considerate of others. Our efforts, perception, and attention should be sharp and precise. And from a combination of these two, our entire outlook on life is transformed.

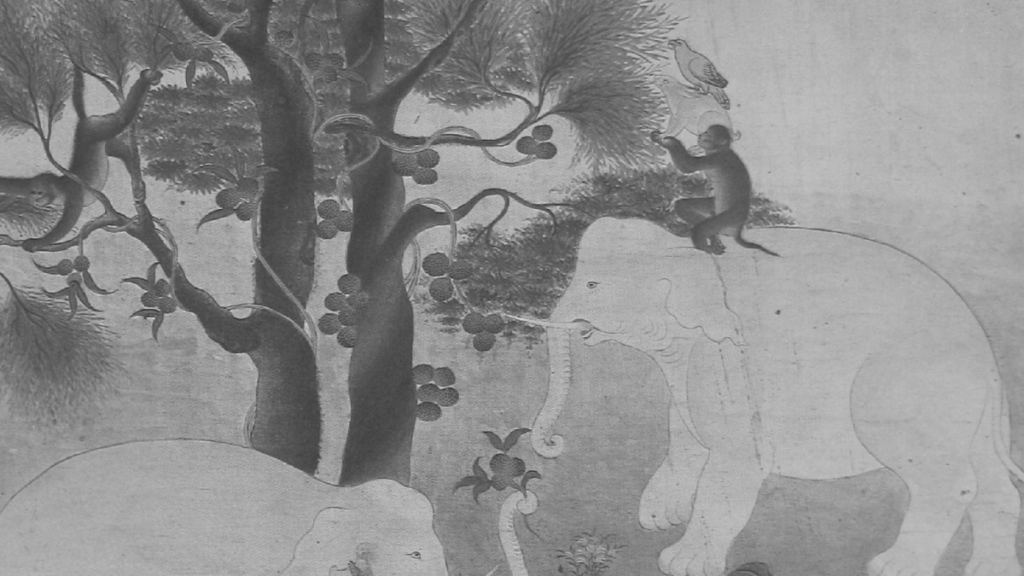

Finally, the Sangha are the nurses. In an ordinary sense, we can see this Sangha as the friends we share the path with and who support us in our way. But the true, noble Sangha, are those who traversed the path and set an example. We can give those people several fancy names like Arhats, Śrāvakas, Pratyekabuddhas, Bodhisattvas. What they all share is the attainment of qualities that prove that the path beyond duḥkha is possible. These are not special people in any way that separates them from us. They are monks, nuns, laymen, and women, from different backgrounds and with different life stories. By seeing their example, we feel inspired that we too can trail this path and achieve final attainment.

These three – Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha – are what we call the Three Jewels and they are the object of an important aspect of Buddhist practice: refuge. In the Lalitavistara Sūtra, we read that “going to the Three Jewels for refuge is a gateway to the light of Dharma.” Going for refuge is, essentially, going for protection. However, we should be clear on what it is that we are protecting and what we are protecting it from.

Essentially, what we seek to protect is our mind. In the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, we read that “the three realms of existence are citta[mind]-only.” If we look closer, we may realize that our mind encompasses most of what we can experience. Both happiness and unhappiness abide in the mind. So it is only logical we would like to seek protection for our minds.

And we want to protect the mind from the mental afflictions. We can subsume our mental afflictions in three main roots: attachment, aversion, and confusion. Whenever we are under the sway of one of those three, we usually end up suffering. And by seeking protection in the Three Jewels, we are releasing ourselves from these three fetters and attending to genuine freedom.

Alright, so we have understood the Three Jewels and decided to seek refuge on them – what comes next? Although I could answer this question in several ways, I believe Buddhist practice can be safely thought of in terms of two main aspects: compassion and wisdom.

Compassion is both a feeling and a method. It is through it that we can access the Buddhist teaching. In his great compassion, it is said that the Buddha offered 84000 teachings for beings according to their needs. Essentially, it means an unbearable wish to free others from their suffering.

Although this may be vaguely familiar in our secular world, we can’t understate the depth of this concept in the Buddhist tradition. Take, for example, the words from Śāntideva in his magnum opus, the Bodhicaryāvatāra: “For all the beings ailing in the world, until their sickness has been healed, may I become the doctor and the cure, and may I nurse them back to health. Bringing down a shower of food and drink, may I dispel the pains of thirst and hunger, and in those times of scarcity and famine, may I myself appear as food and drink.” In the same vein, The Buddha himself said in the Sedaka Sutta: “how does one look after oneself by looking after others? By patience, by non-harming, by loving kindness, by caring (for others). (Thus) looking after oneself, one looks after others; and looking after others, one looks after oneself.” As you can see, this altruistic wish is a seed we nourish deeply within our hearts, and that we call bodhicitta. Through it, we can understand the entirety of the Buddhist path in terms of how to relate to others.

But, how can we have a Buddhist understanding of ourselves? This is where wisdom comes in. Buddhist wisdom can be encompassed in a concept that may be hard to grasp, but in fact is very intuitive: emptiness. The Buddha taught that we see essence where there is no essence, we see a self where there is no self. We mistakenly input a self in what is just a collection of interdependent aggregates. In the Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya, the famous Heart Sutra, we read: “That is why in Emptiness, Body, Feelings, Perceptions, Mental Formations and Consciousness are not separate self entities.” Note that this list of five elements – body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness – constitutes what we call the five aggregates that form the self. To better understand why we say that they are empty, just think of how impermanent each one of these is. Our bodies, feelings, and perceptions are constantly changing. And our impressions about our world and the very consciousness on which they arise is also never fixed. It changes, adapts, and retracts as time and circumstances go by. As Nagarjuna says in his own Letter to a Friend, “it has been said that forms are not the self, the self is not the possessor of forms, a self does not abide in forms, and forms do not abide in a self. Like that, understand that the remaining four aggregates are (also) devoid (of an impossible self).”

I understand this may be a lot to take in and appreciate you reading this far. I have indeed presented you with many different concepts that can be quite deep and complicated. That said, I would like to conclude by telling you something you might not have noticed. Our friendship is, in itself, an expression of Buddhist practice. Why? Well, because Buddhist is all about interdependence and how to relate to oneself and others. What relationship can best qualify wisdom and compassion than that of friends?

In sum, to answer your question, I feel being a Buddhist practitioner means being a friend to the world and being a friend to oneself. We are friends of this world when we take a compassionate approach to our relations. Treating others – including animals – with kindness, love, and compassion. We strive to understand others, don’t ignore them, and don’t get deceived by first impressions – we get to know them deeply. And, in the same way, we take this same consideration and curiosity to ourselves. Because how can we become good friends with others if we are not good friends to ourselves?

I hope this answers your question, my dear friend.

With love,

Alex